Climate Grief

by Hava Chishti, MA

February 2, 2026

Share this entry:

What is climate grief?

As human beings, we are no strangers to grief. Loss and mourning are a part of experiencing life on this planet, and because of that, we are already familiar with grief. Our society and cultures influence norms around how we grieve, and tend to make sense of traditional grief and personal loss, such as the loss of a loved one, largely through our own experiences. But what are we grieving when we talk about climate grief? That depends on who you ask.

A well-known model of the traditional grief process comes from Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a psychiatrist who developed the “Five Stages of Grief” model. Kübler-Ross broke the process of grieving into a sequence beginning with denial and then moving through anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, although Kübler-Ross explained that these stages are not necessarily felt in a particular order, and many people will move back and forth between them. The Kübler-Ross model often resonates with the grief felt in response to the loss of a loved one, but grief that is not as societally normalized, such as climate grief, can struggle to fit within the same model.

Climate grief is often a collective experience. Many times, people who are grieving the changing planet are grieving the same losses together, and can therefore have a stronger connection over that loss. Collective grief, although it stems from feelings of despair, heartache, and deep sadness, can also be an uplifting experience because it allows us to feel connected to others, including people we’ve never met.

Whereas personal loss usually involves a single loss, at one point in time, climate grief can be constant, sometimes repetitive, and ever-growing, with ties to the past and to the future. Climate grief is uniquely challenging because we have to continue living with it as the consequences of climate change grow more present and more personal.

Types of grief

Beyond the Kübler-Ross model, there are other types and models of grief that have been researched and may better represent climate grief, also known as ecological grief. Here are a few:

Anticipatory grief (Dr. Erich Lindemann, 1944):

- Grief that is felt prior to a loss;

- Often experienced as the intersection of anxiety and grief;

- Difficult to manage because the loss has not occurred yet, so it is harder to leave the mourning behaviors and feelings in the past. We are often reminded of the loss that is yet to come (e.g., when grieving a loved one with a degenerative disease, their body is still alive and present, but we recognize the loss of the person as we knew them);

- The passage of time may not heal the feelings surrounding this type of grief since they may become more intense with time.

Ambiguous grief (Dr. Pauline Boss, 1970s):

- Grief that occurs over something that is not a “typical” loss;

- Has a different appearance than traditional loss (e.g., when a loved one is missing but does not have a confirmed death);

- Can cause the grieving process to become stalled because it is not as socially acceptable to participate in grieving behaviors or it may not even be recognized as something to grieve;

- Losses due to climate change can feel ambiguous because they can be slow (e.g., from sea level rise) and intangible. Because of the scale of climate damages and complexity of earth systems, the disruptions to the world that we know and love can feel out of our control, often intensifying the grief;

- Climate grief is not easily defined as one, or even a few losses. It affects everything.

Disenfranchised grief (Dr. Kenneth Doka, 1980s):

- Grief that is not specifically related to death and does not fit within the typical societal acceptance of grief (e.g., the loss of a pet or a miscarriage);

- People who experience disenfranchised loss may not feel comfortable acknowledging their grief in public and have to experience bereavement in private;

- Is often a challenging and isolating experience to go through since people lack the social support that usually accompanies more traditional grief.

The Five Gates of Grief (Francis Weller, 2010s):

- Offers a helpful lens for climate grief, since it highlights how mourning extends beyond personal loss to include the devastation of ecosystems, the weight of ancestral losses, and the disappearance of futures we hoped for. The five gates are:

- First Gate: Everything we love we will lose;

- Second Gate: The Places that have not known love (e.g., parts of ourselves that we hate or bury in shame);

- Third Gate: The Sorrows of the World (e.g., species loss, suffering in the world from wars, famine);

- Fourth Gate: What we expected and did not receive (e.g., disappointment, loneliness, lack of fulfillment or belonging);

- Fifth Gate: Ancestral Grief (e.g., sorrow for the losses of those who came before us).

How does climate grief affect our mental health?

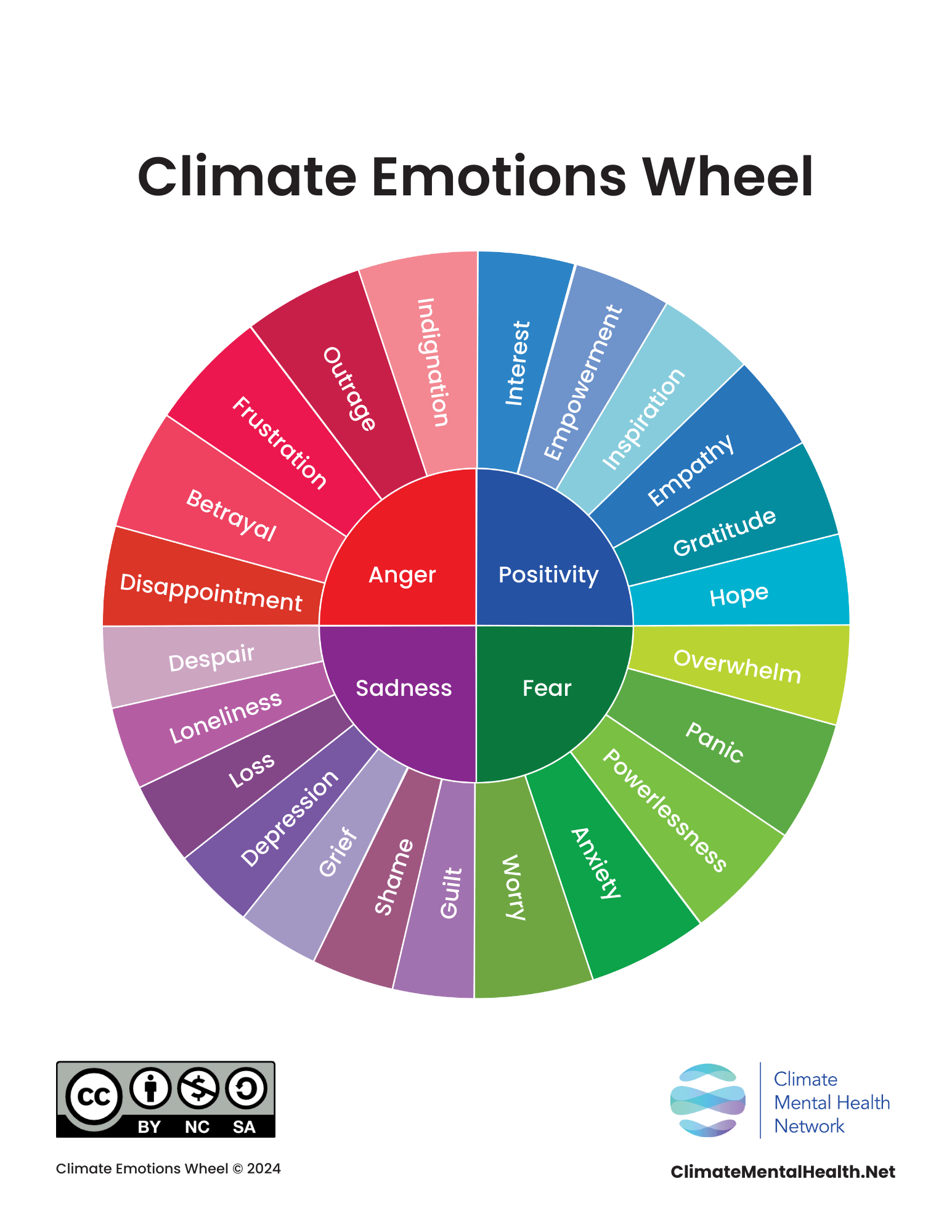

There are many emotions linked to how we process climate change. The Climate Emotions Wheel, developed by Anya Kamenetz, Panu Pihkala, Sarah Newman, and others at the Climate Mental Health Network, helps represent and name some of them.

Grief is a healthy and normal response to loss, and therefore it is a healthy and normal response to climate change. But grief does not often exist on its own – it typically arises in connection with other emotions, like anger, despair, or love, and it can manifest in different behaviours or actions. Some people experiencing grief may become isolated, withdrawing from their friends and family. Others may also struggle with mental health impacts, such as depression, anxiety, trouble sleeping, substance use, suicidal ideation, self-harm, or disruptions to their physical health. In fact, people may experience these heavy emotions or behaviors before they even realize that they are experiencing grief, because the other emotions can feel dominant, overwhelming, and disruptive. This is worrisome for any type of grief, because unprocessed grief can turn into trauma, which can be even more challenging to navigate.

If you happen to be struggling with emotions or behaviors that do not feel positive, you are not alone. As we navigate a more intense world with increasing climate destruction, we are more likely to see certain coping mechanisms and behaviors arise, especially because our society does not equip us with tools to heal or self-soothe in healthy ways, and many of these behaviors can be destructive to ourselves, our health, and our communities. For example, as extreme temperatures become more common, we see instances of increased substance use, suicidality, domestic violence, and cardiac events, among others, which put additional stressors on people, families, and communities.

Unequal impacts on different people

Just as climate grief can express itself in different ways, its origins also differ across populations, demographics, geographies, and lived experiences.

Many people come to their climate grief through directly experiencing climate impacts or loss due to climate disaster, such as the loss of a home, beloved forest, or a loved one due to fire or flood. For these people, climate change no longer feels like a distant problem, but rather an issue that is personally affecting their lives. Entire communities and ecosystems have been and will continue to be lost to climate-related disasters. Especially for frontline and low-income populations with intersecting injustices (e.g., economic injustice, resource shortages, lack of access to government support stemming from classism and racism), the loss of community members and infrastructure is particularly devastating because it is significantly harder to rebuild after a climate disaster (e.g. Ninth ward of New Orleans post-Hurricane Katrina). For those whose lives and identities are closely tied to the land, such as indigenous peoples, farmers, coastal communities, watching climate change decimate your history and livelihood can elicit a deeply-rooted form of grief.

For others, climate grief is a more distant, yet natural reaction to learning about the reality of the climate crisis. Often mixing with other emotions such as anxiety, grief is an expected response to discovering the current and anticipated future loss that climate change brings. Many people who study or work on climate change, such as climate scientists, sit with significant levels of grief in their daily lives, as they are acutely aware about the reality of climate change and understand deeply how it will affect our world, but they see very little action taken by governments and heavy polluters to acknowledge and mitigate climate risks.

Climate grief is also felt uniquely and unequally by different generations. Young people are much more likely to have negative feelings related to climate change than older generations. A 2021 study of youth across ten countries found that the majority of youth are either extremely or very worried about climate change, and many experience negative emotions associated with climate change that impact their day-to-day lives. Younger generations carry more climate grief for clear reasons: they have more to lose from the effects of climate change (job opportunities, resource access, connection to wildlife and biodiversity, a safe and stable planet, and a habitable place to live, to name a few). Many young people are unsure if they want to have children or how to plan for their future, largely because climate change and its mounting impacts continue to exacerbate uncertainty, instability, and risk, to an extent that previous generations have not faced. In tandem, many parents, grandparents, and caregivers experience significant climate grief in thinking about the world their children will inherit.

What can we do to address climate grief?

Climate grief may seem overwhelming to manage, but similar to any other type of grief, there are many ways to face, process, and embrace climate grief.

1. Feel it.

Let yourself feel your climate grief! Talk about it with others. Acknowledge where your climate grief may be coming from.

2. Participate in climate grief community spaces.

What can be most important when feeling grief is to connect with others. Although climate grief may feel like an isolating experience, there are many people struggling to cope with their feelings related to the climate crisis. There are several organizations, community spaces, and opportunities that you can become involved with such as the Good Grief Network, or you could even start your own climate cafe.

3. Engage in climate justice activism.

Although it is not a direct antidote, engaging in climate activism helps attach meaning to life’s work, find joy in purposeful work, connect us with value-aligned communities, and validate our emotions.

4. Find a climate-aware therapist.

The Climate Psychology Alliance North America and Climate Psychiatry Alliance co-host a directory of climate-aware therapists, who have special training in navigating emotions such as climate grief.

5. Mourn the loss.

Mourning is the exterior expression of grief. There are many different ways that humans mourn and signify loss. Loss due to climate change is no different.

Much of mourning is done through the practice of rituals. Mourning rituals can provide structure and guidance to an experience that often feels overwhelming. Rituals that are done with others also promote a sense of belonging and community when one might feel isolated in their grief.

6. Participate in moments or days of collective remembrance.

- Remembrance Day For Lost Species falls on November 30th each year;

- Earth Day falls on April 22nd each year;

- Often communities will organize remembrance gatherings following a large climate event;

- Vigils can be held for climate-related losses, such as holding funerals or memorials for melting glaciers.

7. Training and education.

At both the local, national, and international level, disaster recovery efforts should include grief-aware mental health support and care. Mental health professionals could also be trained to understand the nuances of climate emotions to provide care that is informed and culturally relevant.

8. Find the joy.

There is joy to be found in climate work, and there is even room for joy and hope within your climate grief. Part of the grieving process is allowing yourself to find humor and joyfulness in your life. There is room for all emotions, and there is certainly no benefit from blocking the positive emotions from finding a place along your climate grief journey.

Grief is rooted in love. It is a natural and healthy response to climate change. In a changing world, we can all expect to feel climate grief at some point in our lifetimes. We move forward by acknowledging the feeling, showing up with courage to process it, finding community, and allowing ourselves to feel gratitude for what we still have.

Further reading

Books

Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis by Britt Wray, published in 2022 by Knopf Canada.

Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism by Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, published in 2021 by North Atlantic Books

How to Live in a Chaotic Climate: 10 Steps to Reconnect with Ourselves, Our Communities, and Our Planet by LaUra Schmidt, Aimee Lewis Reau, & Chelsie Rivera, published in 2023 by Shambhala Publications

Human Nature: Nine Ways to Feel About Our Changing Planet by Kate Marvel, published in 2025 by Ecco.

Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief edited by Ashlee Cunsolo and Karen Landman published in 2017 by McGill-Queen’s University Press

Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good by adrienne maree brown published in 2019 by AK Press

What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, published in 2024 by One World.

The Wild Edge of Sorrow: The Sacred Work of Grief by Francis Weller, published in 2015 by North Atlantic Books.

You can also explore collections of books on bookshop.org recommended by the Good Grief Network here and the Climate Mental Health Network here.

Organisations

Here are a few organisations that might help you find resources or direct support to navigate climate grief:

- Good Grief Network

- Climate Cafe NYC (or another climate cafe near you, which you can search for on the web, or check out directories of climate cafes around the world by Climate Cafés here or by Force of Nature here)

- Unthinkable (take a short quiz to receive a tailored list of resources)

- Climate Psychology Alliance of North America

- Climate Psychology Alliance (United Kingdom) (offers support spaces for youth ages 18–25)

- Climate Mental Health Network

- SustyVibes

- Force of Nature

- Eco-chaplains (offers faith-based support)

- Six Seconds – Climate of Emotions (COE)

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance

Music, film, art

WALL-E (2008)

Good Grief: The 10 Steps, a documentary directed by Katie Flint centered around the Good Grief Network, a peer-to-peer support program

Articles and Online Sources

Ecological Grief Resources, Climate Mental Health Network

The anthropologists holding funerals for the world’s dying glaciers, published in Yale Climate Connections by Bridgett Ennis on October 30, 2025

Selected Research/Scientific Papers

Boss, P. (2010). The Trauma and Complicated Grief of Ambiguous Loss. Pastoral

Psychology, 59(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-009-0264-0

Calabria, L., & Marks, E. (2024). A scoping review of the impact of eco-distress and coping with distress on the mental health experiences of climate scientists. Frontiers in psychology, 15, 1351428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1351428

Chishti, Hava, “Grieving Climate Change: A Psychological and Personal Exploration of

Emotionally Processing the Climate Crisis” (2023). Pitzer Senior Theses.159. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/159

Cunsolo, A., Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Clim Change 8, 275–281 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

Doka, K. J. (2008). Disenfranchised grief in historical and cultural perspective. In M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, H. Schut, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Handbook of

bereavement research and practice: Advances in theory and intervention. (pp.

223–240). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14498-011

Doka, K. J. (1999). Disenfranchised grief. Bereavement Care, 18(3), 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682629908657467

Fulton, G., Madden, C., & Minichiello, V. (1996). The social construction of anticipatory grief. Social Science & Medicine, 43(9), 1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00447-5

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E. R., Mayall, E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863-e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Khatana, S. A. M., Werner, R. M., & Groeneveld, P. W., et al. (2022). Association of extreme heat and cardiovascular mortality in the United States: A county-level longitudinal analysis from 2008 to 2017. Circulation, 146(3), 249-261. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060746

Le, K. (2025). The impacts of extreme heat days on the prevalence of domestic abuse. SAGE Open, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440251317797

Nori-Sarma, A., Sun, S., Sun, Y., Spangler, K. R., Oblath, R., Galea, S., Gradus, J. L., & Wellenius, G. A. (2022). Association between ambient heat and risk of emergency

department visits for mental health among US adults, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry,

79(4), 341-349. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4369

Pihkala, P. (2024). Ecological sorrow: Types of grief and loss in ecological grief.

Sustainability, 16(2), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020849

Sekowski, M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2022). Associations between symptoms of prolonged grief disorder and depression and suicidal ideation. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12381

Sweeting, H. N., & Gilhooly, M. L. M. (1990). Anticipatory grief: A review. Social Science & Medicine, 30(10), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90293-2

Author and version info

Published: February 2, 2026

Author: Hava Chishti, MA

Editor: Colleen Rollins, PhD